A doorbell rings in a patient's room. A monitor swivels around, showing a real-time video of a nurse making her rounds for the day.

"Good morning, Mr. Rhodes. How are you doing this morning?" the nurse asks, her eyes scanning a number of screens that show her patient's vital signs and notes from his electronic health record.

These rounds-by-video may seem like something out of the future. But they're already in place at Mercy Hospital in St. Louis County. The hospital's parent organization is banking on the idea that virtual medicine is more efficient, leads to better quality of care and could soon become the norm.

The Sisters of Mercy Health System, headquartered in Chesterfield, debuted a $54 million dollar virtual care center with an open house Tuesday. The space will house 330 employees and allow for dozens of doctors and nurses to use video conferencing and other tools to care for patients across four different states at any one time.

Virtual care helps stretch resources where they're needed, said Dr. Gavin Helton, who directs the center’s outpatient program. Monitors can be installed in patient's homes to supplement care from a home health aide. Rural hospitals can have easier access to more specialized physicians, who tend to cluster in larger cities. On night shifts in the intensive care unit, virtual care can act as another set of eyes.

"The human interaction is valuable and can’t be replaced but being able to do it virtually, I’m able to have contact with multiple patients, all basically at the same time." Helton said.

"This is very cost effective," said Thomas Hale, Mercy Virtual's executive director. "You can move electrons around rather than bodies."

Even though Medicare and other insurance providers don't fully reimburse for the service, Hale said the program helps Mercy hospitals reduce readmissions and improve other quality measures required by the Affordable Care Act.

"For every dollar you spend monitoring people in the ICU, you save $4 in cost because of decreased length of stay, decreased mortality and morbidity," Hale said.

Mercy Virtual is a central location for four programs:

- Mercy SafeWatch, which is used to monitor patients in intensive care units.

- Telestroke, which allows neurologists to see patients who are exhibiting stroke symptoms in community emergency rooms that do not have an on-site specialist via telemedicine.

- Virtual Hospitalists, which allows doctors to order tests and read results for patients.

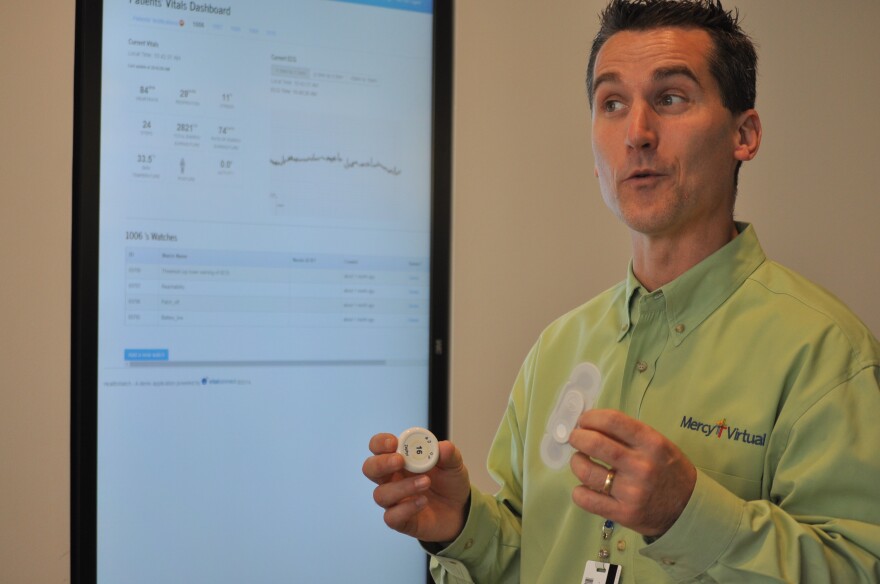

- Home Monitoring, which places monitoring equipment in the home, so patients can have regular check ins if they are chronically ill following a hospital stay.

The programs housed at the new facility are already incorporated into hospitals across the Mercy Health System, but Mercy Hospital spokesperson Bethany Pope said the Virtual Care Center is built to expand their capacity as needed.

Follow Durrie on Twitter: @durrieB.