A bill sitting on Gov. Jay Nixon’s desk that would authorize Missouri school personnel to carry guns has at least one teachers group up in arms.

The sponsor of the provision says it’s designed to help protect schools in areas where police response to a shooting may take too long to be effective.

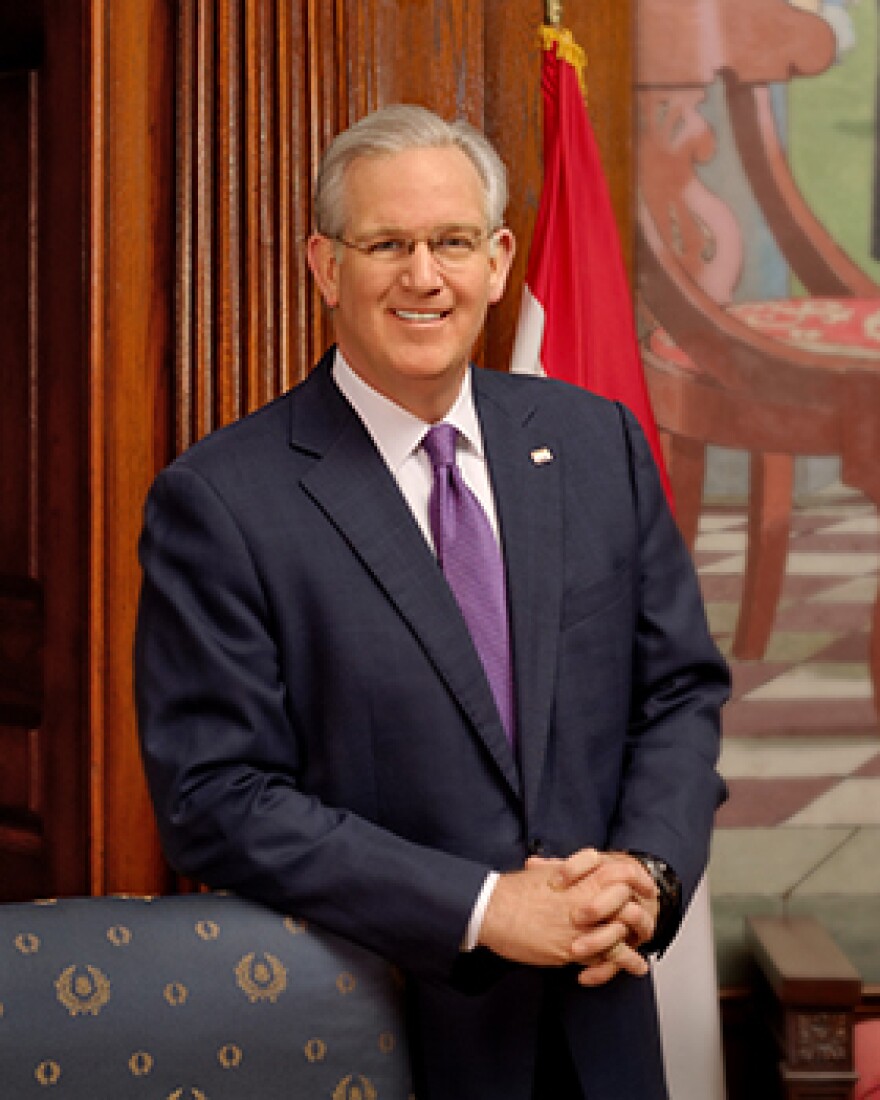

Nixon, who came out strongly against guns in the classroom after the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut in 2012, isn’t saying what he’ll do with the legislation that awaits his action. It contains numerous provisions affecting the state’s concealed-carry law.

But there is no shortage of opinion on both sides.

“The reason for it is to give schools another tool in their toolbox to provide security for their schools,” said state Rep. Kevin Elmer, R-Nixa, who put the teacher language in the bill. “It is up to the discretion of the local school boards whether or not they will take advantage of this particular tool.”

Otto Fajen, legislative director for the Missouri National Education Association, says guns and teachers don’t mix, and if schools need armed protection, they should hire law enforcement professionals.

“It raises profound concerns about safety,” he said, “in terms of people not knowing who’s armed. That can create some uncertainty.”

And Kim Weber of Columbia, who heads the Missouri PTA, says teachers should be able to concentrate on their students, not on making sure firearms are stored and used properly.

“There are too many unanswered questions,” she said. “How would they be secured? Who would have access to them? Would they be on their person? Would they be locked in a cabinet? Would they be in a special room? As a parent, I would have to have all of those things explained.”

What the law says

The legislation, Senate bill 656, won final approval in the last week of the legislative session. It loosens some restrictions on carrying concealed weapons and lowers the age for eligibility for a concealed-carry permit to 19 from 21.

One major change in the legislation would allow any school district in Missouri to designate one or more elementary or secondary school teachers or administrators as a voluntary “school protection officer.” Such a designation would include the right to carry a concealed firearm or a “self-defense spray device.”

Before it decided to allow such a designation, the board would have to hold a public hearing on the matter. Records of what school personnel have been designated as protection officers would not be available to the general public, though they would be available to law enforcement agencies.

The bill would allow trained teachers or administrators to become school protection officers and carry a gun.

School protection officers would have to have their weapons in their personal control at all times; failure to do so could be grounds for removal from the classroom and dismissal altogether.

Those seeking to become a protection officer would have to have a concealed-carry permit and pass a training course. Once they gain the designation, they would have the authority to detain or use force against someone on school property when deemed necessary, even against a student.

Resources and response time

Because local law enforcement will know who has been designated as school protection officers, even if the public can’t find out, the risk of confusion at seeing an armed adult among students during a shooting situation would be minimized, Elmer said.

“The public and the students do not know who the armed teachers are,” he said, “but they're reporting back to local law enforcement, and they know who the armed individuals are in the schools after the extensive training this individual has gone through.”

Having such trained individuals already in the schools could be a big help, Elmer added, particularly in rural areas where authorities may not be able to respond to a violent situation quickly.

If a district cannot afford to hire its own armed officers, he added, having teachers and administrators properly trained in using firearms is a good alternative.

“For some school districts,” Elmer said, “they just don’t have the resources to pay for police to be on staff. This allows the local communities to have these discussions and figure out whether or not they want to take advantage of this option. If it doesn’t fit them, they don’t have to do it.

“It does give those who would be comfortable in moving forward to provide a teacher, after extensive training and certification, to be in the schools as an anonymous individual armed with protection. I think they should have that right to do that.”

In his home city of Nixa, Elmer added, resource officers from the sheriff’s department and the police are in the schools.

“Obviously,” he said, “if you can afford that, I think that’s a better option.”

Paul Fennewald, a former FBI agent who also served as Missouri’s director of homeland security, now heads the Missouri Center for Education Safety.

He agrees that giving local districts, particularly those in rural areas where police response may take relatively longer than it does in more heavily populated regions, is a reasonable option.

“In areas where it’s more of an urban area,” he said, “where law enforcement response is relatively quick, we see less of a local support for something like this.”

In any case, Fennewald said, the designation of school protection officers would have to be voluntary, not required, and proper training is crucial.

“We know, historically, that with an active shooter, the longer they’re in a school, without law enforcement responding, the death toll goes up,” he said. “So in a rural area, when there’s an armed person in the school, it may make a difference. I don’t know. We haven’t seen any instances where that’s actually happened yet. But it may.

“In a more populated area, an urban area where law enforcement is going to be on the scene in a matter of minutes, it probably doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

Safety, uncertainty and liability

Opponents of the bill say it doesn’t make much sense in any case. A recent survey on school safety by a St. Louis-based group called SchoolReach, which helps schools reach out to the public in emergencies, appears to confirm that view.

It found that 64 percent of the districts responding had not considered allowing members of their staff to carry guns. Another 8 percent had considered but rejected the idea, while 10 percent said they had hired armed law enforcement personnel to patrol school grounds and 4 percent had non-armed personnel doing the same.

After the shooting in Newtown, Conn., Nixon came out forcefully against arming teachers, saying in a letter to the state’s school superintendents:

“Putting loaded weapons in classrooms is quite simply the wrong approach to a serious issue that demands careful analysis and thoughtful solutions….

“Current law also allows local school boards to prohibit guns in their classrooms. This is a time-tested and solid foundation that we should reinforce, not undermine.”

A spokeswoman for the governor said that his views on arming teachers have not changed, and the bill passed by the General Assembly “will get the same careful and comprehensive review given to every bill that gets to his desk.”

Others are more direct in their reaction.

Brent Ghan, with the Missouri School Boards Association, said in an email that “we are pleased that the authorization of school protection officers is not a state requirement but is left to the local school board to decide. We think a public hearing on the matter is appropriate. We also think the training requirement included in the bill for school protection officers is essential.

“We are concerned about the liability this bill may create for local school districts and we will be recommending local boards of education take that into consideration before authorizing school protection officers. We also share the concern that parents would not be able to know if a classroom teacher has a concealed weapon in a classroom.”

Don Senti, head of EducationPlus – formerly Cooperation School Districts – said flatly:

Schools 'need to be the safest environment for our children to learn in.' -- Kim Weber, Missouri PTA

“I agree with what virtually every safety officer in the state has said, that it is just a wrongheaded thing to do. The security and safety of schools should be left up to properly trained and certified officials.”

Fajen, with Missouri NEA, wonders whether it’s the right approach to give teachers one more duty to worry about during school hours, even if they take it on voluntarily.

“There are concerns that someone who is a full-time educator might have so many things going on that there might be a situation where they would lose possession of a weapon,” he said. “They could be taken by surprise or leave it somewhere by mistake, or something happened where it was no longer in their possession, because they have a whole other job to do....

"We’d like to keep all the work done in education being done by professionals who get to focus on what it is they are doing. This strikes us as an inappropriate mingling of those things. We have really urged that they not pass this into law."

He is also concerned about potential liability for districts, schools and individuals.

If schools are that worried about security, he said, a better tack to take is to use a “full-time, dedicated law enforcement professional who is identified as such, so that people know. There’s clarity about that.”

Weber, with the Missouri PTA, notes that her daughter teaches elementary school in outstate Missouri and is so concerned about security of her personal belongings that she doesn’t even bring her purse into the building anymore because someone took her driver’s license once “out of spite.”

“These kinds of things happen every day in a school,” Weber said. “I just don’t think there is any safe place to keep guns stored….

“Our schools should not have staff members armed. They need to be the safest environment for our children to learn in.”