Since Saturday’s fatal shooting of Michael Brown, St. Louisans have been trying to understand and deal with what happened.

How could a college-bound teenager with no history of violence or criminal behavior end up shot to death by a police officer in his own neighborhood? St. Louis Public Radio’s Véronique LaCapra and Tim Lloyd went to look for answers and to find out what people in Ferguson are doing to cope.

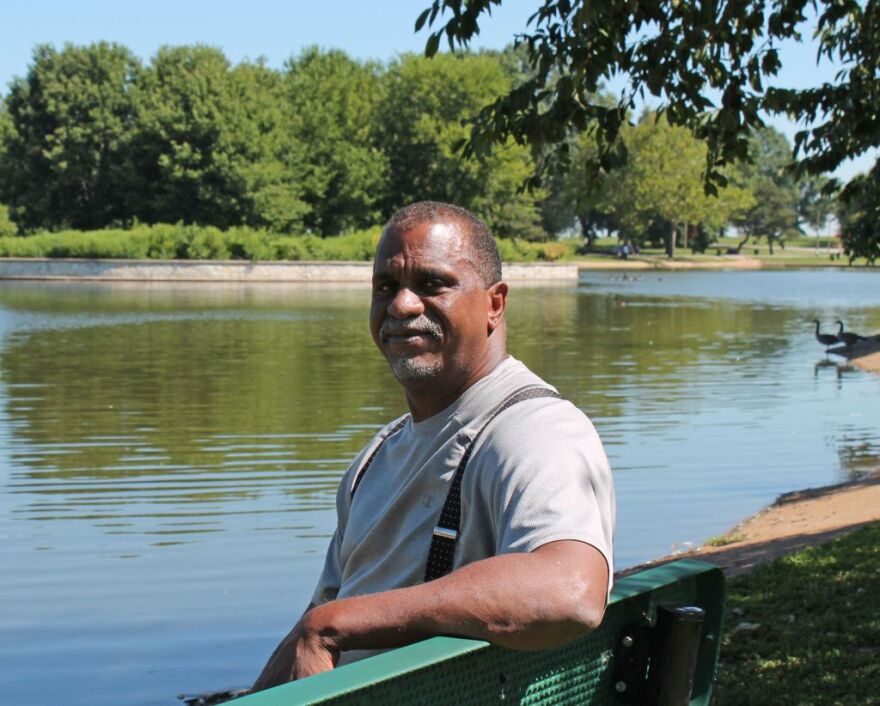

Véronique took a step back from the tragedy to speak with Saint Louis University developmental criminologist Norman White about some of the long-standing, systemic problems that led up to Brown's shooting and its aftermath.

Tim spent time with psychologists and mental health professionals rushing to provide services to residents in Ferguson and beyond who are shaken by recent events.

You can listen to what Véronique and Tim found out, here:

Or, scroll down for more photos and for excerpts of Véronique's interview with SLU's Norman White.

VL: So we’re talking today because of the situation in Ferguson. But we’re not in Ferguson. We’re in the O’Fallon neighborhood, in a park actually, in North St. Louis. Why are we here?

NW: Because the struggles in Ferguson are no different than the struggles in O’Fallon Park or in The Ville or in Northwood or any of the other communities in this part of St. Louis.

The communities have been left in a position where kids are growing up in what I call being “in risk.” That they are challenged in their daily lives by stressors from family, from peers, from the schools they attend, the institutions they interact with, from police.

And the kids in the developmental literature that experience that are at greater risk for involvement in more serious delinquency, serious violent behavior.

So they’re disaffected or disconnected — not attached to the mainstream — primarily because we’ve placed them there.

VL: Just to be clear, from what we know about Michael Brown, he didn’t have a history of violent or criminal behavior. He was actually headed for college. So how did someone like him end up in a deadly confrontation with the police?

NW: There are communities that are — because of the crime problems, because of the gang involvement, because of the violence that’s associated with lots of kids that are at risk or in risk — police begin to over-police. They stop everybody. Every kid becomes a possible offender.

VL: Some of the reaction to Michael Brown’s shooting has been violent. And not all of that violence has been directed at the police. There’s been looting. There’s been destruction of property. Why is that?

NW: There are kids who are just angry. I did an interview a couple of weeks ago with a guy who said to me, you know, you get it. That it’s essentially the roots of our bitterness. It’s the police stopping us. It’s the poverty we deal with every day. It’s the schools where we don’t feel like we fit in. It’s people looking at us as though there’s something wrong with us and we don’t belong.

That anger simply has found a place to be released at this moment.

VL: The problems we’re talking about aren’t unique to Ferguson.

NW: Lots of kids are poor. But the problem here is that race is overlaid in this. And that’s a significant part of the anger that’s going on.

That it’s about racial profiling, it’s about, for example, you drive in your car and a cop’s sitting along the side of the road, and you drive by him, and all of a sudden, they pull out, and they just drive behind you. And they drive behind you for blocks. They drive behind you for a mile.

And it could be benign, the reason that they’re there. But it doesn’t feel like it’s simply benign. It feels like, “I’m trying to send you a message that I’m here, and I’m watching you.” And that’s not something that kids are comfortable with. It’s not something that most adults are comfortable with.

Our problem is that we don’t talk about it between races most of the time. So I talk with other African-Americans that are older, my age — I’m 60 years old — that have these same issues. But we don’t sit down across the table from people that don’t look like us and have these conversations.

And that’s where the change will come.

Follow Véronique LaCapra on Twitter: @KWMUScience

Follow Tim Lloyd on Twitter: @TimSLloyd