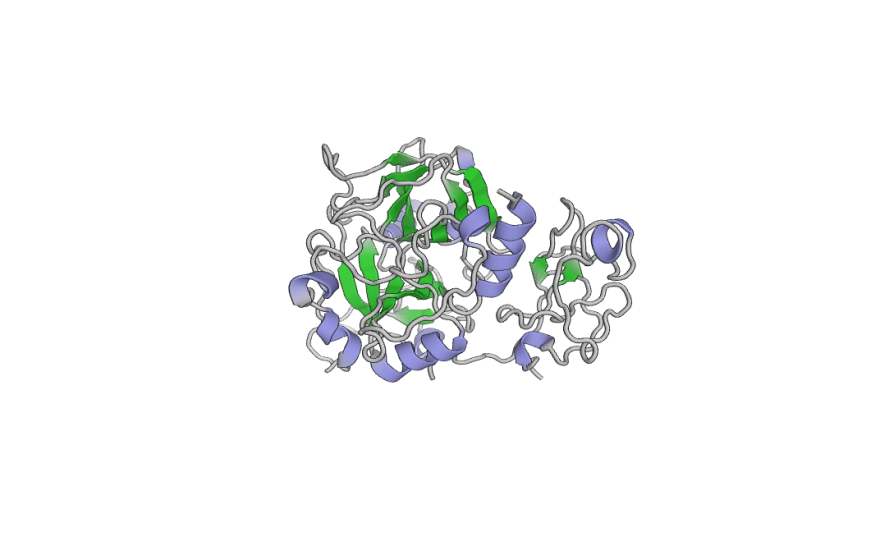

It took three years for Dr. Enrico Di Cera and his team to map prothrombin, the protein that causes human blood to form clots. They ran countless samples through a machine, trying to find the conditions that would form a crystal large enough to be seen by a specialized X-ray.

“That’s the part that’s like cooking, not an exact science,” Di Cera said, at his laboratory at Saint Louis University on Thursday.

After Di Cera’s team managed to crystallize prothrombin, a high definition X-ray generator shot electrons toward the sample over and over to create images from all angles. Mapping protein structures is a crucial step in the discovery of new treatments for common illnesses.

The process generated terabytes of raw data, the vast majority of which would generally be discarded soon after the results were refined and published.

“By doing that you may lose some of the original features. If you discard the original data sets, you will never be able to go back,” Di Cera said.

Instead, Di Cera’s team uploaded that raw data to a new online repository that is helping shift structural biology research into the big data era. The Structural Biology Data Grid, headquartered at Harvard Medical School, pools 173 datasets from different cell structures mapped by labs throughout the world. The information is spread among servers at a number of institutions.

Two research labs at Washington University in St. Louis have also contributed data, including one protein structure mapped by microbiologist Niraj Tolia that's involved in the transmission of malaria.

“This type of data has never been deposited before,” Tolia said. “The most direct benefit is the ability for other scientists who use this type of data to improve their analysis methods. We can share our data so they can use it for their own inferences, and it improves the speed and time for people to share information.”

Further, Di Cera said, raw data from past experiments could be re-examined in the future by scientists with improved imaging techniques.

Di Cera and Tolia are authors in a paper outlining the Grid, which appears in the journal Nature this month.

Follow Durrie on Twitter: @durrieB.