This article first appeared in the St. Louis Beacon, Oct. 23, 2013: Bill Lowry considers himself to be a “pretty low-tech guy – no iPhone, no apps, any of that stuff” – so he thought it was pretty ironic that he is teaching the first class at Washington University’s entry into the growing field of internet education.

Dubbed Semester Online, the program joins Washington U. with other schools, including Emory, Northwestern and Notre Dame, for online instruction that is less open, less massive than the so-called MOOCs – massive online open courses -- that have been popping up all over in recent years.

Those courses can have thousands of students signing up to watch lectures and take part in online discussions with students from all over the world. They have no admissions requirements, but they usually don’t cost anything or lead to any credit toward a degree.

The students who take Lowry’s class on environmental and energy policies, or courses offered by any of the other schools in the Semester Online consortium, get credit at the university they attend; the courses are covered by the tuition they pay.

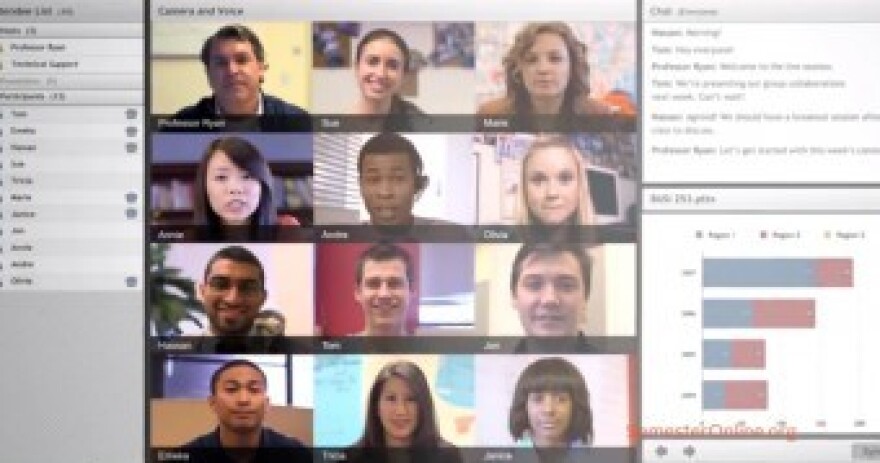

They view 80-minute recorded lectures once a week, on their own schedule, then attend an 80-minute virtual class where they can see the professor and their fellow students, and everyone else can see them, in a set-up that looks a little like the set of Hollywood Squares or an expanded Google hangout.

Lowry says that the personal interaction is in some ways stronger than it would be in the large lecture setting though he admits he can’t tell what may be going on in a student’s room away from the computer’s camera.

“There is no place to hide,” he says. “You’re looking right at them and they’re looking at you and there’s a lot of eye contact. It’s almost tiring when you get finished with an hour or an hour and a half of one of these sessions.

“It’s something new for me, and I wasn’t quite sure how it would work. It’s been a real education.”

Real education taught in a new way was what Washington U. and its colleagues in Semester Online were after, according to Edward Macias, who left his longtime position as the university’s provost earlier this year and is overseeing the school’s venture into online learning. And, he said, the university wanted to proceed with caution.

During this fall’s debut, just 17 Washington U. students are enrolled in a Semester Online course. Lowry’s class has 19 students, including nine from its home campus and 10 from other schools. The section he teaches in the more traditional way has many times that, with a waiting list.

Macias said he didn’t know what to expect, in terms of demand, from the initial semester of the online experience, but he knew that he wanted the rollout to be measured.

“We wanted it to be small,” he said. “We wanted it to just get started.”

Even though the program is brand new, Macias said schools are already becoming used to the format.

“We’re learning a lot,” he said. “The faculty is getting comfortable with this teaching method, and the students have had their first chance to try such a course. The university itself is learning how to handle these things, and we have eight schools in the online consortium and we’re learning how to work together.”

More courses are scheduled to start next semester, from Washington U. and the other schools, with Lowry’s course joined by ones on critical earth issues and an introduction to psychology. Students who want to venture virtually onto other campuses can learn about the Old Testament at Brandeis, baseball at Emory or Shakespeare and film at Notre Dame.

Students at any university may apply to take the courses, after consulting with their academic adviser at their home campus to make sure the course fits into their program and will result in credit. In some cases, the course will be covered by their regular tuition; in others, additional payment may be needed.

How will the schools know whether the online courses are working as well as traditional ones? Macias said that a formal assessment of student learning from the computerized offerings will be conducted in the spring.

“That’s the name of the game,” he said. “Did they learn well in the online environment? How does it compare with how they learned in a traditional class. That will show us a lot.”

Duke bows out

The Semester Online consortium originally had nine member schools, but arts and sciences faculty members at Duke University voted in April to drop out, though Duke quickly said it remains committed to online education even though it would not be part of this program.

"Faculty control of the curriculum is the foundation of the university, and the lengthy and vigorous debate over the Semester Online proposal illuminated a number of important issues that are also central to the future of higher education," Provost Peter Lange said after the vote, according to a statement from the university.

"While the Arts and Sciences Council rejected the recommendations of its faculty committee, we believe there is great value to our students and faculty in incorporating online learning into the Duke experience, and Duke will continue to work to expand opportunities do so in the coming months. We will also continue to innovate across the disciplines to provide our students with a rich array of educational opportunities.”

Before the close vote, concerns were raised that joining Semester Online had not gone through the proper faculty channels. Critics said they were worried about signing up with a private company, 2U, which developed the program, and wondered whether they would have the control over courses that they needed.

Supporters said Duke should be taking part in what they considered to be a small experiment in a growing field, an experience that could provide insight into how universities can best be effective teaching online.

After defeating the Semester Online motion, Duke’s arts and sciences faculty council passed a resolution stating its commitment to continuing the school’s "current practice of exploring and adopting a variety of online platforms."

Different reception at Washington U.

Macias and Lowry say the faculty’s attitude toward Semester Online at Washington University has shown acceptance and curiosity instead of the opposition characterized by the vote at Duke.

“There has been a lot of interest from faculty,” Macias said. “They are more familiar now with online learning, and they have this process going on where can learn from their own colleagues.”

Lowry has learned of that interest firsthand.

“Walking around campus,” he said, “I have people come up to me, even people I don’t know, introduce themselves and ask about online education.”

They do have concerns, though, Lowry added. Basically, they fall into areas like genuine concern whether students are getting high-quality instruction, worries about whether online courses will lead to a smaller number of professors and questions about the financial impact on the university as a whole.

As far as the first issue, Lowry said he is pretty sure the quality of learning by students in the online course is comparable to what they get in more traditional settings. The other issues are more long-range, so answers aren’t likely to come for a while.

He does admit that he isn’t sure whether there has been enough of a dialogue between the administration at Washington U. and professors who may not be sure of the value of moving their courses online. “Some are more skeptical,” Lowry said.

If Kristen Chin’s experience is typical, that kind of skepticism doesn’t extend to students in Lowry’s class. The junior from Boston, who is majoring in environmental policy, says she particularly enjoys the weekly sessions when all of the students gather virtually.

“We have pretty interesting conversations,” she said. “Nothing is different except for the fact that you don’t see the other people live.”

Except for another student in the class who is a personal friend, Chin said she hasn’t gotten together physically with any of her fellow students. But they have gathered outside of class on a Facebook-like page where they can share articles and other resources.

What doesn’t she like about taking a class online? Chin hesitated for a moment, then admitted she couldn’t come up with anything. She said if another course is offered online that she is interested in, she wouldn’t hesitate to sign up.

But, she added, she doesn’t see online education taking the place of a more traditional college experience.

“Nothing will ever replace having a physical space where you can come together and study together and talk together and laugh together,” Chin said.

“It’s a wonderful supplement to the rest of your classes, and you can do extra learning on your own. That’s wonderful, but I don’t think anyone should ever take all their classes online.”

For all of Lowry’s enthusiasm, his outlook is similar. If he could teach a course the traditional way or through Semester Online, what would he choose?

“I’d probably teach it on campus,” he said. “I do like the classroom atmosphere. But the technology is pretty good, and the learning is pretty comparable.

“I think it’s working pretty well. I’ve learned a lot. It’s been worthwhile. We’ll see what happens.”

Expanding slowly

That wait-and-see attitude comes across strongly in a conversation with those at 2U who are in charge of Semester Online.

Andrew Hermalyn, general manager of the program, told the Beacon that with a little more than 100 students taking 10 courses in the debut semester, the experience has been generally positive. He said some students who may have expected an easy time academically may have been disappointed.

“One of the things we have learned as we worked with students,” he said, “is that the majority of students are finding their Semester Online course just as rigorous – or in some cases harder – than their on-campus courses.”

With the discussion sections capped at 20 students, everyone gets the chance to get to know everyone else, he said.

“The combination of the small classes and a lot of interaction with the professors has truly ended up with an experience that has not happened before,” Hermalyn said.

The spring offerings will total 19, he said, and the deliberate pace of the growth should help make sure that the quality of the learning and of the students’ experience remains solid.

Asked to compare the Semester Online model with the more widespread MOOC model, Hermalyn said there is room for both, but the two approaches have significant differences.

“In a word,” he said, “I would think MOOCs are all about distribution. I would say Semester Online is all about outcomes, ensuring the quality and the rigor of the courses and making sure that students get a really unique but also a compelling experience.

“If they complete a course successfully, they get credit from a really great university. They have something to show for it at the end of the day.”