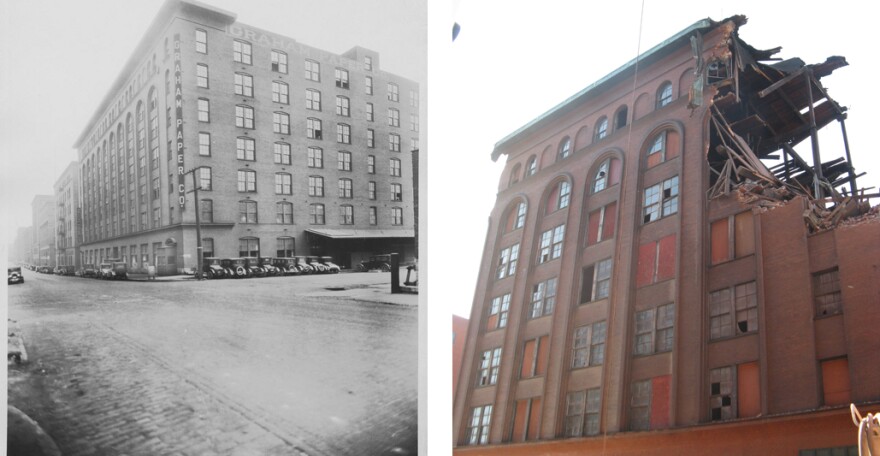

There’s now another hole in the urban fabric of downtown St. Louis. Piles of rubble are all that remains at the corner of 11th and Spruce streets, where the Cupples 7 building once stood.

The 113-year-old brick warehouse was part of the Cupples Station Historic District, a massive complex of 20 buildings that served as the logistics hub for the city in the early 20th century. Today, just eight remain.

As Rachel Lippmann reports, the demise of Cupples 7 is prompting the city to reconsider the role it plays in historic preservation.

Orphan building

Back in 2006, developer Kevin McGowan and his business partner were rehabbing downtown buildings left and right. But Cupples 7 was one they never wanted.

"There were three buildings left, 7, 8 and 9," he says. "But we put no value at all on our offering price of Cupples 7, because half of the roof was in the basement when we bought it. It was the most dangerous building I'd been in to that point."

But at the height of the housing bubble, McGowan couldn't pass up the prospect of acquiring two buildings that could be turned into high-end lofts and retail space. So he took the deal.

Even in that era of easy financing, he couldn’t get anyone lend the $1 million it would cost to put a new roof on Cupples 7. And then the economy tanked.

"Every avenue that existed, either at the city level, the state level, the federal level, any financing level, it was explored," McGowan said. "But no one was willing to do anything. It just didn’t make sense."

The building's condition was already so deteriorated that the city condemned it in 2008. McGowan's company eventually stopped paying taxes. And it continued to languish without a roof.

So in November 2011, McGowan applied for a demolition permit, saying he had no choice. It was denied, as was his appeal. Over the next two years, Cupples 7 continued to decay. A last-ditch effort by the city to find someone with enough cash in hand to immediately stabilize the structure failed. So on May 6, building commissioner Frank Oswald issued an emergency demolition permit.

A preventable loss

With Cupples 7 gone, preservationists like Michael Allen have turned their attention to another historic brick warehouse - the Crunden-Martin building just south of the Arch grounds.

A 2011 fire left the building without a roof. That's the exact situation that hastened the demise of Cupples 7, and is illegal in the city.

"The city has the power to do something here - they're just not using it," Allen says. "This property owner needs to be brought into housing court, the fines need to accrue. Individuals who don't repaint their garage doors on alleys can sometimes get fined every month until they comply with the law. That's not happening with Crunden-Martin. There’s just sort of a neglect of these larger buildings, and a vigilance on the smaller level."

But Allen wants more.

"We cannot rely on developers and banks and lenders to pull these buildings back together," he says. "We need private fundraising, we need city government strategy." And he may get it.

"Largely reactive."

"We have reacted very positively, and very aggressively to preserve buildings," says Jeff Rainford, the chief of staff to Mayor Francis Slay. "But I will the first to say that under this administration, we have be largely reactive."

Rainford says the city does not have the resources to be a developer.

"If we were to spend money on rehabbing a building, we could do one building," he says. "So our focus is where we can, where we have the ability to do it, is to waterproof buildings."

So-called "mothballing" isn't a new idea. (In fact, it's encouraged by the National Park Service, which oversees the National Register of Historic Places.) The Old North Restoration Group did it to the 146-year-old Mullanphy Immigrant Home on the south edge of the neighborhood after two walls collapsed in separate storms.

The building remains vacant, but executive director Sean Thomas says spending the money was still a good decision.

"A vacant building that’s boarded up and secured is much better for the neighborhood than one that is unsecured and crumbling," he said. "The other value is that many of these buildings have a character and a look that makes them distinctive and landmarks in many neighborhoods."

Most projects won't be as expensive as the Immigrant Home, which required the building of two new walls, and was completed only because contractors donated about $150,000 in labor and materials. But the biggest hitch is always money.

Rainford says the Slay administration is looking at boosting the fines related to historic preservation, and directing some of the revenue to a mothballing fund.

"But people do need to understand that at the end of the day it’s going to take private investment to save these buildings, and the private investment interest, if we're going to be realistic about it, is not going to be there for every single one of these buildings," he said.

But, he adds, the city learned from the fate of Cupples 7 that it needs to do more to keep as many buildings standing for as long as possible.

Follow Rachel Lippmann on Twitter: @rlippmann