The economy needs babies, but working women are often told that having kids will hurt their careers. So, researchers from Washington University in St. Louis have crunched the numbers: Ladies, at least when it comes to finances, waiting until you’re 31 might make a difference.

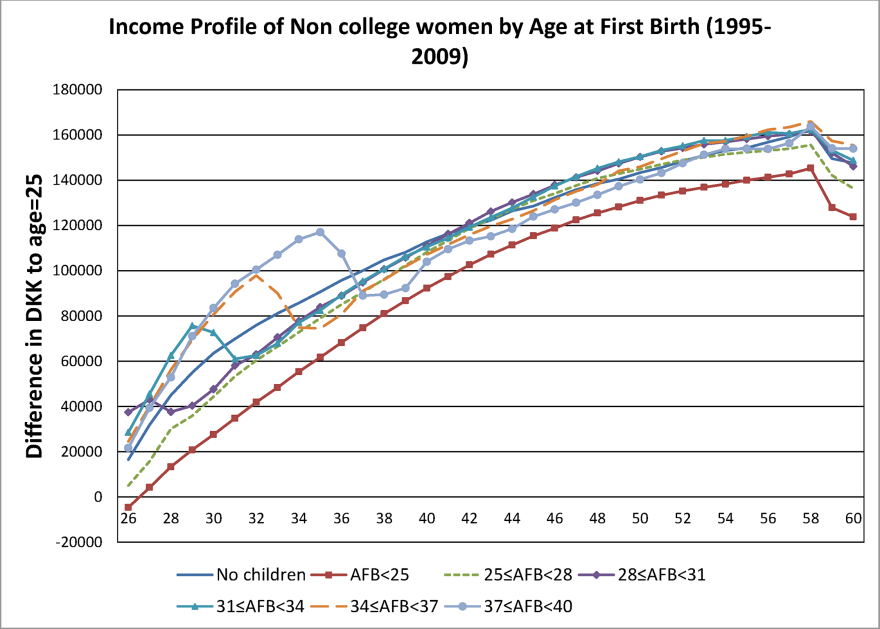

The study pulled data from a Danish government database with information on the lives of 1.6 million women. Those who had their first child before the age of 25 lost about two years’ worth of wages over the course of their careers, even more if they did not attend college. But women who had children after the age of 31 earned more over the course of their careers than those who never had kids.

“Establishment in your profession before going into pregnancy, that is going to give you a higher lifetime labor income later on,” said Man Yee Leung, the study’s primary author.

In bothDenmark and the United States, women earn less than their male counterparts for doing similar work, according to the World Economic Forum. (The White House puts the number for American women at $0.79 for every dollar a man makes.)

Working mothers frequently scale back hours at the office after having kids, which can also hurt their earning potential. Raul Santaeulalia-Llopis, a WashU economics professor who co-authored the study, said the Danish data suggests that women whose careers are interrupted by having children in their twenties may be less likely to be promoted later. That could help explain why those women lose the equivalent of two years' worth of paychecks over their career-span.

“I was actually expecting this figure to be even higher, if we consider that most of the important career promotions that individuals face (tenure-track decisions, partnership in law firms, etc.) happen in the mid-30s in the U.S.,” Santaeulalia-Llopis wrote in an email.

So what does this mean in the U.S.?

Both researchers believe the results would be more pronounced if the same study were conducted here. Unlike Denmark, the U.S. does not require employers to grant paid maternity leave. Danish women receive at least 18 weeks of paid leave for the end of their pregnancies and after the birth of their children, plus additional leave that can be split with a partner. Further, American women who continue to work earn more later in their careers than Danish women do, said Santaeulalia-Llopis.

“This means that in the U.S., women have potentially more labor income to lose,” he wrote.

In addition, the wage disparity between women who do and do not attend college is significantly larger in the U.S. than in Denmark. This suggests American women who become mothers early on and do not attend college would see even lower earnings over the course of their careers, Santaeulalia-Llopis said.

What if you’re a man who’s working and thinking of having children? Those studies have already been done. Even without giving birth, you’ll earn more over your lifetime than your friends who don’t have kids, a trend that economists like to call the "Fatherhood Premium."

Follow Durrie on Twitter: @durrieB.