Julian Mosley Jr. was the second African-American to graduate from Washington University School of Medicine, which had been in existence for more than 80 years when he received his medical degree in 1972. Ten years earlier, Dr. James L. Sweatt had been the first.

“I think that happened because, among blacks, the Washington University medical school was perceived not only as traditionally white and expensive, but also as requiring almost impossibly impeccable credentials,” Dr. Mosley said last year. “Even well-qualified blacks didn’t think they would have much of a chance.”

Every 10 years was not good enough for Dr. Mosley. While still in med school, he began his dogged quest to ensure that the medical school increased its output of black doctors.

He began actively recruiting other black medical students and throughout his life he continued to do so. He became a long-standing member of the med school’s admissions committee.

In 1979, Will Ross, M.D., who is currently the medical school’s dean of minority affairs, was one of Dr. Mosley’s recruits. Dr. Ross was a Yale undergraduate at the time.

“He said ‘you belong here in St. Louis,’” Dr. Ross fondly recalled. “He was very convincing. I owe him a debt of gratitude. Julian had stories of what it was like for him and wanted the institute to become more embracing of people of color.”

He succeeded. More than 300 black doctors have now graduated from the medical school.

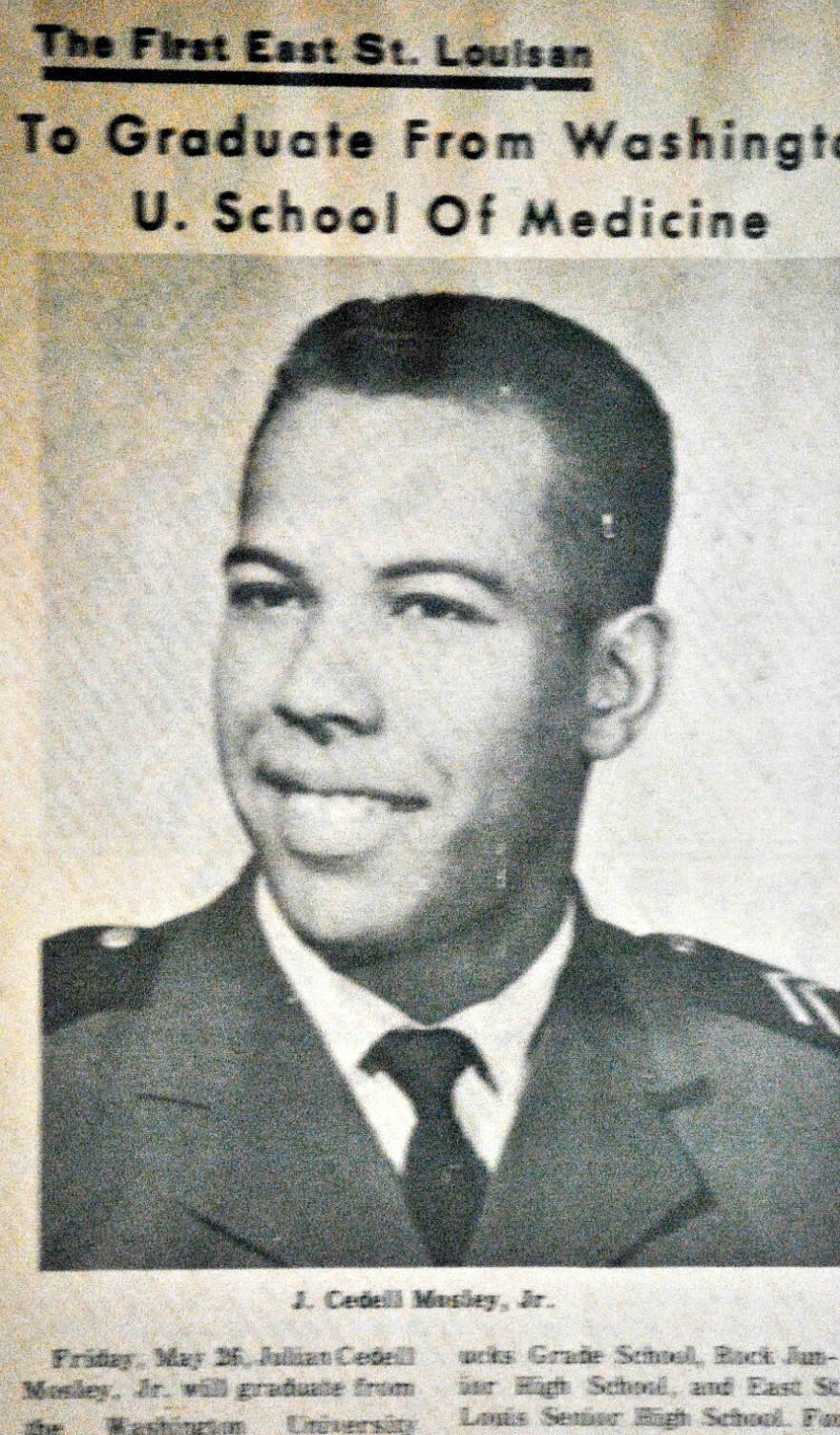

An East Side Boy Makes Good

Julian Cedell Mosley Jr. had always wanted to be a doctor. It was a big dream for a black kid growing up at the intersection of Gaty Avenue and 26th Street in East St. Louis, even in the city’s golden years.

He was born on April 2, 1944, in St. Louis at St. Mary’s Infirmary, the first private, full-service hospital to allow black physicians to admit their patients. They nicknamed him Mickey because he cried like a little mouse. Mickey was the only child of Julian Cedell Mosley Sr., who was known as Cedell, and Thaddeus (”Thad”) Scott Mosley, who was named for her father.

Like thousands before them, his parents had joined the Great Migration of blacks to the north for better jobs and to escape Jim Crow. His mother came from Mississippi. After marrying Cedell Mosley Sr., she managed her nearby grocery store and rental properties before becoming a full-time homemaker.

His father, who came from Alabama, became one of the few black police officers on either side of the Missippi River in the metro St. Louis area. He rose steadily through the ranks of law enforcement to become chief of police and later the city’s public safety director. He retired as head of security for a Metro East bank.

Dr. Mosley was in the first class to have African-American students at East Side Senior High School, from which he graduated in 1962. He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in chemistry from Saint Louis University in 1966. After becoming the first East St. Louisan to graduate from the Washington University School of Medicine, he became the first African-American to be chief surgery resident at the old Jewish Hospital of St. Louis.

The Surgeon Who Opened Doors

After graduating from Saint Louis University, Dr. Mosley was a research chemist at Anheuser-Busch Brewery in St. Louis, followed by a medical internship, residency and his chief residency at the old Jewish Hospital until 1977. His fourth year of med school included delivering babies during an obstetrics/gynecology rotation at Homer G. Phillips Hospital, St. Louis’ premiere training ground for black doctors for more than 40 years, until it closed in 1979.

Dr. Mosley became a surgeon and went into private practice in St. Louis in 1977. He partnered with Frank O. Richards, M.D., at Near North Central Surgical Practices until Dr. Richards’s retirement. He continued as a solo practitioner until shortly before his death of prostate cancer on Sept. 21, 2016. He was 72.

During the 1990s, Dr. Mosley worked with other physicians and community leaders to help reduce cancer in blacks through education. He cited smoking, environmental pollutants and lack of knowledge of health care options as being among the chief culprits.

He made inroads in both his community education and academic recruitment efforts. But despite his success, Dr. Ross said that Dr. Mosley remained “a very unassuming person.”

“He didn’t always talk about the doors he opened,” Dr. Ross said. “He gave lots of homage to those who came before. He was well respected by the academic community as well as the community in general.”

A Legacy of Love

Dr. Mosley was a member of the St. Louis Medical Society, the Mound City Medical Society and Eta Boulé, a professional men’s organization. A fair amount of his spare time was spent watching St. Louis sports teams and attending track and field meets, particularly the Drake Relays at Drake University in Iowa.

Dr. Mosley, who had lived in the Central West End for many years, never forgot his roots. He asked that his remains be scattered in the Mississippi to show how his life spanned the two sides of the river — and to show his love of both.

He was married for 13 years to the former Sheila Stern (later Stix, now Bader), whom he met while both were undergraduates at Saint Louis University. They had one child.

Dr. Mosley was preceded in death by his parents.

Among his survivors are his wife, Annetta Booth, his son and daughter-in-law, Julian (“Jay”) C. Mosley III and Roxann Barnes Mosley of Los Angeles, and their two children, Chloe Juliauna Mosley and Harper Ella Jillian Mosley.

A memorial service is being planned and will be announced at a later date.

Memorial contributions may be made to the American Cancer Society, 4207 Lindell Boulevard, St. Louis, MO 63108.

Gloria S. Ross is the head of Okara Communications and AfterWords, an obituary-writing and design service.

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org.

Support Local Journalism

St. Louis Public Radio is a non-profit, member-supported, public media organization. Help ensure this news service remains strong and accessible to all with your contribution today.