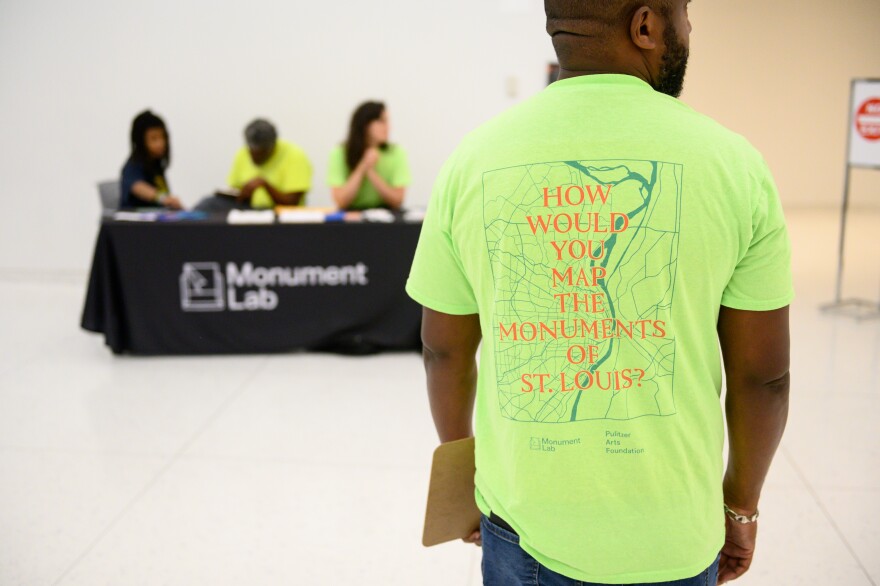

Many people attending festivals, visiting the Gateway Arch or simply strolling the streets of St. Louis last summer received a simple request: Draw a map of St. Louis and mark any monuments or important sites. Feel free to suggest new monuments that should be built.

The result is a cache of 750 hand-drawn maps. They present wildly different views of the city and attitudes about living here.

Some maps celebrate famous sites like the St. Louis Zoo and the statue of St. Louis himself atop Art Hill in Forest Park. Others point to things that have been removed from the landscape, like the mounds built by native Mississippians.

Another shows a street map of downtown St. Louis with notations for “incidents of racism, from microaggression to racial violence.”

Monument Lab, a Philadelphia-based organization that studies how communities remember their histories through public art and monuments, spearheaded the project. The group was in residence for two years at Pulitzer Arts Foundation, where representatives trained local researchers to go into communities and solicit maps.

The goal was to see which sites loom largest in St. Louisans’ mental pictures of the city.

In July, Monument Lab published online all of the maps, plus interpretive essays about them and a map that compiles trends from the submissions. Also publicly available are searchable databases including each of the thousands of individual sites referenced on the maps, including new monuments that participants proposed.

An evolving understanding of history

This trove of data comes during a national reckoning over statues and other public monuments and memorials that is playing out in St. Louis as well.

“One of the most important aspects of the debates around monuments is recognition that these are not fixed aspects of history. They are not unchangeable,” said David Cunningham, chair of Sociology at Washington University.

Cunningham and teaching assistant Alia Nahra led a class through a semester-long study of the maps last year.

“These objects have been placed for a reason at a particular time. And when we think about St. Louis,” Cunningham said, “one of the things is the many ways in which our history has been fluid, in terms of the commemorative landscape.”

An example of this evolving relationship with history is seen in the abrupt June removal of the statue of Christopher Columbus from Tower Grove Park, following years of debate and study. More than 1,000 people have signed an online petition calling for removal of the statue of the city’s namesake on Art Hill and the renaming of the city.

Cunningham also cited the 2017 removal of a Confederate monument from Forest Park, as well as the 1959 transfer of a monument to Union Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon from a prominent midtown location to what is now known as Lyon Park, in a less trafficked corner of the city.

He said the move followed St. Louis University’s purchase of an adjacent tract of land with a donation from a daughter of Confederate Gen. Daniel Frost, who required that Lyon’s monument be removed.

Different views of the same city

Many who submitted maps identified their age, ethnicity and ZIP code.

The maps display a view of the city that is divided by race, said Geoff Ward, a professor of African and African American history at Washington University who has studied historical patterns of racialized violence. The students in his course Monumental Anti-Racism studied the maps.

Student Megan Lamaire "pointed out that mapmakers who self-identified as white tended to have a proprietary orientation toward the city,” he said. “Just communicating a sense of belonging, a sense of comfort and inclusion.”

Mapmakers of color often communicated a different impression of the city, he said.

“Their maps focused on places that were lost, like Mill Creek Valley or the history of Kinloch or what was lost in Kinloch,” Ward said. “Those maps tended to convey a sense of social distance or alienation relative to the maps of white respondents.”

One Arch, many views

The site included most frequently on the maps was the Gateway Arch. Most mapmakers included it as an unambiguous source of pride. Others used it as a window through which to gaze at enduring inequalities.

“The Arch was so frequently mentioned but also in many ways was something that people wanted to grapple with a little bit and if not erase entirely, to minimize its presence,” said Nahra, who now works for the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University.

A sign of the city’s evolving relationship with its past can be seen in something as simple as the formal name of St. Louis’ iconic monument.

The Gateway Arch was completed in 1965 as the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial — a celebration and remembrance of the nation’s expansion across the continent, a process that included the violent displacement of native peoples and the continuation of the intercontinental slave trade.

In 2018, the National Parks Service changed the landmark’s name to the simpler Gateway Arch National Park.

This name change accompanied a more inclusive and accurate view of American history reflected in the monument’s interpretive center, Ward said.

The park service website now describes the site as “a memorial to Thomas Jefferson's role in opening the West, to the pioneers who helped shape its history, and to Dred Scott who sued for his freedom in the Old Courthouse.”

Ward said these changes represent an acknowledgement of “the violence, the injustice, the crimes against humanity that are bound up with the project of westward expansion.”

He said this ongoing process is necessary for the nation to build “a culture of trust and cooperation” that would make it possible to undo legacies of racial violence.

“We really require a shared truth that can replace the myths we tell about ourselves, about our country, our history,” he said, “with a truth that acknowledges the reality of our past and our present.”

Follow Jeremy on Twitter: @jeremydgoodwin

Our priority is you. Support coverage that’s reliable, trustworthy and more essential than ever. Donate today.

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org.

Got a news tip? Send it to Jeremy D. Goodwin.

Support Local Journalism

St. Louis Public Radio is a non-profit, member-supported, public media organization. Help ensure this news service remains strong and accessible to all with your contribution today.

![James Bragado tests out a mobile sound monument that was designed to elevate the types of music heard in predominantely Latino neighborhoods. [6/6/19]](https://npr.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/00a2e98/2147483647/strip/true/crop/4032x2667+0+178/resize/130x86!/quality/90/?url=http%3A%2F%2Fnpr-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2Flegacy%2Fsites%2Fkwmu%2Ffiles%2F201906%2F060619_JDG_monumentF_01.jpg)