In the dog-eat-dog world of music radio, Lou “Fatha”Thimes Sr. was top dog for a very long time.

“In broadcasting you’ve got to be able to contend with all types of personalities, your boss, the program director …” said the veteran disc jockey, leaving the sentence dangling in the 1999 book of biographies, Lift Every Voice and Sing. But, he added: “Broadcasting is a beautiful field. I’ve loved every moment of it.”

Mr. Thimes got his start in 1952 while serving at Kadena Air Base on Okinawa in Japan. His captain was looking for someone to play black music on the base radio station. He parlayed his Army experience into a 50-year radio career here in his hometown.

He was at the mic during the segregated ‘50s that tumbled into the turbulent ‘60s when Sam Cooke presaged A Change Is Gonna Come; he was there in the ‘70s when Marvin Gaye asked What’s Going On? and he was still around in the ‘80s when the digital age began to change radio and the nation. He played the blues until he could not.

Mr. Thimes, whom his son, Lou Thimes Jr., said had been in declining health for some time after suffering a fall during the past year, died Wednesday (June 11, 2014) at SSM Physical Therapy in St. Louis. He had lived downtown until recently moving to the McCormack House At Forest Park Southeast. He was 85.

Funeral services at New Sunny Mount Missionary Baptist Church are being planned.

“The death of Lou Thimes reminds us that a certain notable generation of radio broadcast pioneers is quickly taking their leave,” said Tom Ray, co-owner of Vintage Vinyl.

“His trademark radio voice,” Ray added, was like “going down into the deep blue sea.”

It’s what made him a “personality” when radio was looking for distinctive personas to attract black listeners. That and his knowledge of music, a natural kindness, an instinct for what appeals to the masses and a regal bearing that worked well outside of the sparse studios few listeners ever saw.

The industry got more than it bargained for with Mr. Thimes. He was “an extremely influential figure in the St. Louis community,” said Art Silverblatt, a communications professor at Webster University. “For years, the Fatha led the African-American community in an ongoing celebration of its culture.”

In this youtube selection, you can hear Mr. Thimes working during a snowstorm in 1999.

Fatha, Fatha, Fatha

When Mr. Thimes returned from Japan, he could not shake the radio bug. He began broadcasting from the John Cochran and Jefferson Barracks veterans’ hospitals.

In 1958, he joined KATZ-AM 1600 three years after the station came on the air. On Saturdays, he primed the souls of churchgoers for Sunday with gospel music. He was soon stirring another kind of soul.

“I guess I had a good enough voice,” he told the St. Louis Journalism Review in 2010, “because soon they took me off the gospel show and had me playing rhythm and blues.”

His sonorous baritone provided the show’s rhythm; broken hearts and hard times did the rest.

“The blues is reality,” he said. “It happens to everybody.”

When B.B. King wailed “The Thrill is Gone” or Bobby Bland lamented “Ain’t No Love in the Heart of the City,” Mr. Thimes would rhythmically intone “Fatha, Fatha, Fatha!” If the music got too hot, he’d say, “Don’t po’ no water on me, just let me burn!”

Despite being a good singer, a talent he passed along to his daughter, jazz vocalist Denise Thimes, he would deliberately mutilate “Happy Birthday” on-air to the delight of the audience honoree.

“(Black deejays) were doing the science and art of radio,” said Lou Thimes Jr., who followed his father into radio as ‘The Real J.R.’ “With his commanding presence on the microphone, he could control his listeners.”

It wasn’t mind control, it was “camaraderie with his audience” said Bernie Hayes, a fellow radio personality and Webster University media professor. “It was his ability to communicate through song, music and his own soul.”

Mr. Thimes honed his communications skills as a stand-up comedian. He performed with the late John Smith in a team known as Lou and Blue. The duo worked with such notables as Tina Turner, Albert King, Lawanda Page and Redd Foxx.

The latter two almost secured him the role of Grady on the hit sitcom, Sanford and Son. He lost out to Whitman Mayo, a decidedly less imposing figure.

Believe the Lou

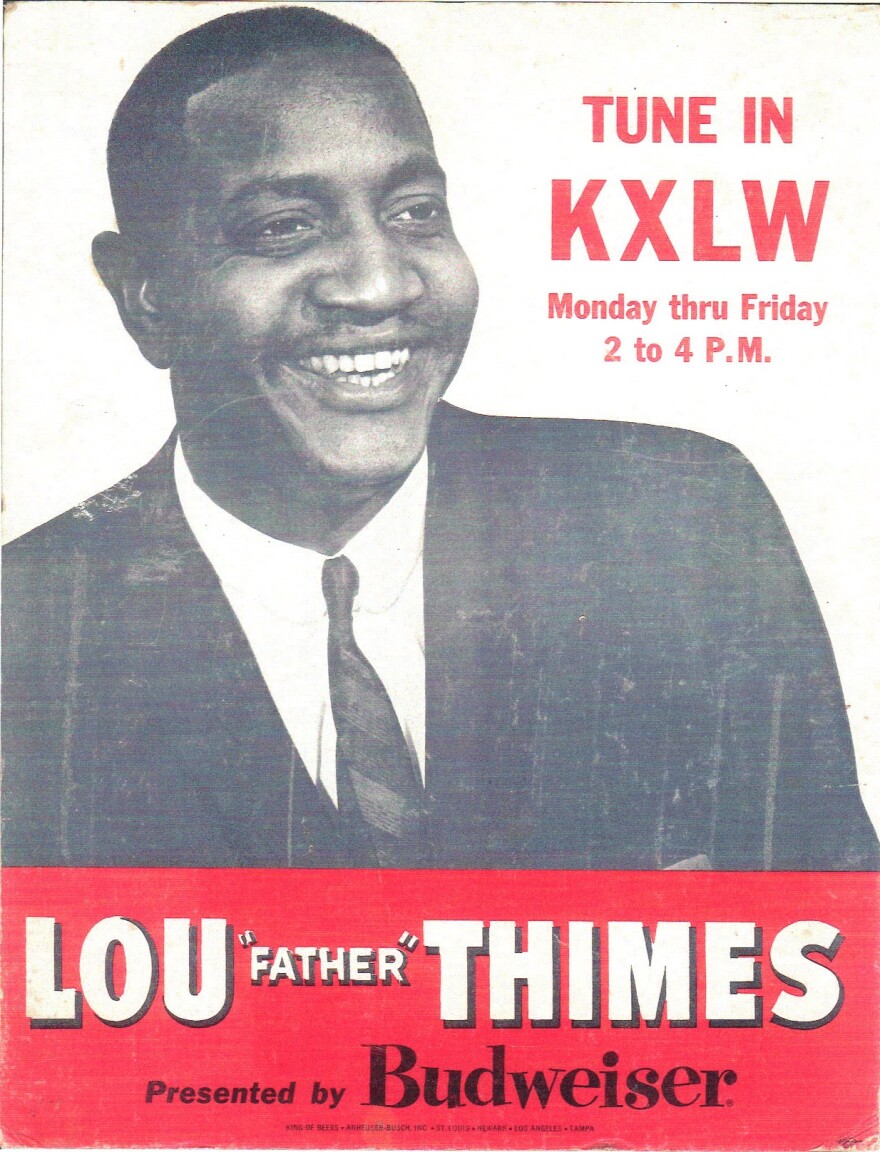

In 1960, KXLW lured him away from KATZ, and through the years he would bolster the audience at radio stations KADI, KXLW, KKSS, KMJM, WESL and KDHX. He eventually returned to KATZ, where he spent the bulk of his legendary career.

Silverblatt thought Mr. Thimes’ shows worthy of syndication. He drew fans from throughout the Midwest and South.

“(They) listened religiously to his programs and came to St. Louis by bus to ‘party hardy’ with the Fatha live at the Charles Shaw Hall,” Silverblatt said. “He educated young white listeners about rhythm and blues,” helping to make them fans of African-American culture.

“Lou Thimes was a culture hero for the black radio

Wherever he was, he would implore listeners to “Believe the Lou when he tells you …” Along with the music, he dispensed pearls of wisdom, chimes of laughter and melodious affirmations.

“Lou Thimes was a culture hero for the black radio audience and for teens black and white that fell under his sway in the 60s and 70s,” said Ray, a 27-year KDHX radio host.

The two worked together briefly at KDHX, Mr. Thimes’ final radio gig, but Ray had long been an admirer. He’d seen Mr. Thimes in action with music stars who came to town: Mavis Staples, Bobby Bland, B.B. King, Solomon Burke, who recorded the hit Cry to Me.

Once, Ray recalled, Burke said that Mr. Thimes was the man who generously drove him around in his car introducing him to everybody he needed to know.

“You could tell (the artists) appreciated that here was someone who played their music,” Ray said.

“I’ve worked with some of the greatest artists in show business,” Mr. Thimes modestly admitted.

For the first couple of months at KDHX, Mr. Thimes worked with the nonprofit station’s executive director, Beverly Hacker. She was his producer, feeding him his music selections.

“Lou would bring in this big stack of CDS and say ‘I guess I’ll play this next;’ (then he would) pick the perfect song to go after that,” Hacker said. “He put together music so beautifully by memory. He was a true professional and his love of the music absolutely came through the radio.”

Keeping his day job

Mr. Thimes was among the first St. Louisans to be elected to the board of the National Association of Television and Radio Announcers.

His many honors included the 2010 St. Louis Blues Lifetime Achievement Award and the St. Louis Radio Hall of Fame Legacy Award.

But radio was just his “hustle,” a side job. The volatility of the radio business ensured that he did not quit his day job.

For more than 40 years, Mr. Thimes worked for the Human Development Corporation of Metropolitan St. Louis and the city’s License Collector’s office.

“He worked radio around his ‘real’ job,” which was a clerk, said his son. “With a big family, he knew he had to keep a regular job.”

That meant nightclubs and overnight shifts and weekends at the radio station.

Shortly before becoming a civilian radio personality, in the mid-1950s he was the first African-American ring announcer at Kiel Auditorium boxing matches.

He was a restaurateur, a love second only to radio. During the mid-80s, Mr. Thimes operated a small barbecue restaurant on Martin Luther King Drive. Before that, he ran “Fatha’s Pork House,” which closed after a security guard was killed. He opened his final restaurant in 2011; it, too, was marred by tragedy. He had planned the Lou "Fatha" Thimes BBQ Pork House with his youngest daughter, Patrice Thimes. Shortly before it opened, she was killed by a stray bullet.

Later, gator!

Louie Edward Thimes Sr. was born Oct. 18, 1928, and was raised by his mother, Mauldine Thimes, in the heart of St. Louis. He graduated from the old, segregated Booker T. Washington Technical High School. He went to Lincoln University on a basketball scholarship.

“That is the only way I got there,” he said. “My family was poor with no money.”

His future wife, Mildred Dewalt, once declared her lack of interest in marrying a “tall, skinny man.” They had been married more than 40 years when she died in 1997.

Mr. Thimes opened each show with “Keep a smile on your face because the more you smile, the more you improve your face value.” His signature signoff was: “Be good to your neighbors. Speak. If nothing else, just leave them alone. I’ll be seeing you later, gator!”

In addition to his wife and daughter, he was preceded in death by his parents, his brother, Evans Ford, and two sons, Edrick Thimes and Reginald Thimes.

In addition to his son, Lou Thimes Jr., and his daughter, Denise Thimes, his survivors include two other daughters, Deborah Thimes and Kelly Thimes, all of St. Louis.

Send questions and comments about this story to feedback@stlpublicradio.org.

Support Local Journalism

St. Louis Public Radio is a non-profit, member-supported, public media organization. Help ensure this news service remains strong and accessible to all with your contribution today.